When I started my current job at komoot at the end of 2022, I did some thinking about the type of stories that the community on our platform find most inspiring and engaging. One of the best examples was Quinda’s ‘The Netherlands’ biggest circle‘, which had been really popular. A quirky and unique idea, which was visually appealing and relatable, because it made you think – I wonder what this would look like in another place?

Her concept was simple: what was the biggest circle you could possibly cycle in the Netherlands? She made the route, and then went out to cycle it with impressive efficiency – knocking out the 590 km route in 36 hours.

Hook, line, and sinker, my imagination was captured. As you might have noticed, I’m already rather susceptible to strange bike tours that create shapes on the map. I suppose in many ways, that is what my cycle around the world was. I started and finished in the exact same spot, and yet saw around 50,000km on my way between home and home. That’s what almost all my bike rides are: a ride from my front door with who-knows-what in between. Sometimes it’s no more than a shimmy to the local supermarket. Sometimes it’s a sprint out to the Kent lanes after work. Occasionally it’s a really long ride, like the one that took me to Wales and back in a weekend.

Perhaps my first dabble with ‘lines on the map’, was when I rode the Prime Meridian searching for as many meridian markers as possible on the way down. First, I pedalled it from Greenwich to the South Coast, and then the following year from Grimsby back down to Greenwich in one (slightly masochistic) 300km day out.

There are plenty of other examples of this. Take the individuals obsessed with Wandrer, the many creatives producing ‘Strava art’ or the amazing concepts like Alice’s straight line across the length of the UK.

After seeing Quinda’s ride, I couldn’t help but wonder what the biggest circle one could cycle in the UK would be. After a little Googling, I couldn’t find any evidence of someone trying to find out, and I thought that finding out would be a fun way to explore komoot’s functionality.

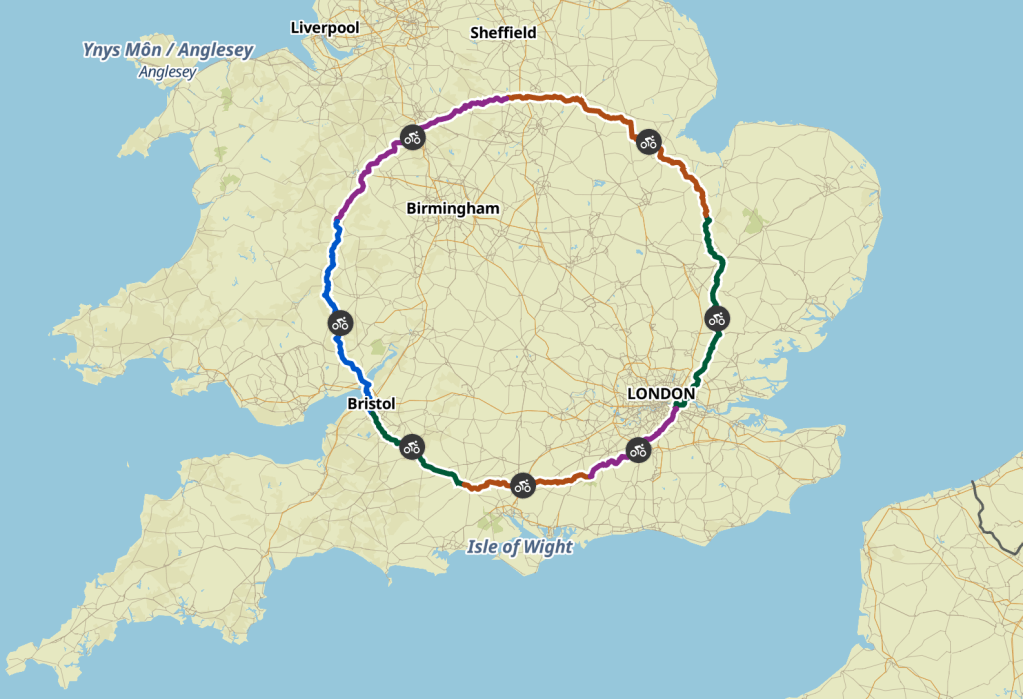

After a little testing, I concluded that my Giant Circle should start in London. It could perhaps have been made slightly larger by skirting just north of the capital, and navigating the Mersey and river Dee around Liverpool, but the resulting route wouldn’t be as geometrically pleasing to the eye. There was also something quite romantic in the notion of starting at the coordinates 0.0, 0.0, but perhaps more importantly, something undeniably convenient about it, considering that Greenwich was just a 20 minute cycle from my house.

At 900 km, it was not a little circle. When I initially came up with the idea, I thought it would be a ‘fun’ experiment to see if I could knock it out in 3 days. But that was when I was feeling much more fit, certainly more motivated, and it hadn’t been quite so long since I’d done any days resembling that kind of distance on a bike.

I knew I was leaving my house-share at the end of April, hoping to spend the rest of summer abroad, and suddenly my weekends were looking rather limited. I also wanted to squeeze in quite a different type of bikepacking trip, with a MTB crossing of Wales while I still had the chance.

And so, I figured that I could at least start by picking off the sections in segments. The first third heading clockwise from London has a few opportunities for direct trains back to the capital, and with a little logistics I might be able to do the rest without a) needing to take time off work and b) riding any silly distances. This would also mean I could take my time a little and document the recce properly.

I began with a day ride from London to Haslemere with some friends and former colleagues. Josh, who I cycled the Old Chalk Way with, and Ali, who I cycled my second meridian trip with as part of Apidura’s Parallels campaign.

The weather forecast looked ominous, but we’d booked the day in advance and each of us was too stubborn to call it off. I regretted that almost immediately.

To begin with, the viewpoint at Greenwich Observatory was closed off behind ugly fencing while the area was renovated, meaning there would be no ceremonious photo at the start. Within barely 20 minutes of cycling, I flatted, before we’d even made it past Blackheath common and just as the rain began to fall again.

We persevered, heading out through the drab suburbs of South London that I know unfortunately well, before diving into a cafe to try and warm up. We sat sipping large cups of coffee while puddles from our wet clothes formed beneath us, watching the rain hammer down outside.

Ali decided he’d had enough not long after we got back on our bikes. Fair enough. A ride all the way back to North London from here was already grim enough in this weather, he said. We subbed him out for Rob, Josh’s friend who we rode with for a section of the Old Chalk Way in late 2022. Rob already looked suitably unimpressed, a face full of regret for having agreed to join us on this soggy excursion. He lasted a grand total of about half an hour with us, until we reached Banstead Downs racecourse before heading home for a warm shower and a cuppa.

As is usually the case with rain, it’s simply a matter of exercising enough patience. The sun does appear eventually, and as we reached the Surrey Hills we finally had some respite from rain. It wasn’t just our feet that were in puddles in our shoes – many of the roads were completely flooded. One was entirely impassable, and we had to mount a fence and stomp over a boggy field to find rideable tarmac again.

I tried to strike a balance on this route, between finding nice roads that were suitable for skinny wheels, whilst also staying true to the circle. As a result, there were the occasional sections that were a little less inspiring to ride, although they still added to the character of The Giant Circle. One of these sections was the ride along Portsmouth road on a bumpy bike path, which is absolutely worth it for the tranquillity that follows around the Devil’s Punchbowl.

I stopped recording at Hindhead, and we veered off the route to catch the train home from Hindhead for our respective afternoon commitments in town. We hadn’t even cycled 100 km but it had felt considerably longer.

A week later I was back at it, this time for a solo ride from Hindhead to Salisbury. Once again, the weather forecast was looking like a tedious series of spring showers. The trains were cancelled to Haslemere, so instead I rode over from Farnham before continuing west. A delightful day followed with a wonderful tailwind, across the top of the South Downs National Park along windy country lanes. A few of these were familiar to me from the Amesbury Amble audax route, which over the years has become my go-to 300 km loop, wriggling through charming Wiltshire villages.

I enjoyed riding through Winchester town centre, along its cobbled streets lined with tourists. From there it was back onto wide open plains, dodging the odd shower while leaning back into the accompanying tailwind. It blew me all the way to Salisbury – a town I know little about other than it has a massive cathedral and was the scene of the infamous 2018 Russian spy poisoning – where I hopped on another train back home. Another 100km in the bag, and yet I’d only still cycled less than a quarter of The Giant Circle.

A fortnight later I rode the leg to Bristol, this time accompanied by my friend Phil. The very same Phil who cycled around Oman with me 5 years ago. This setting could not have been more different, with the British spring seeming very reluctant to bring anything other than more rain.

Salisbury was a convenient meeting place, with a direct train from both Bristol and London. The segment was a good length too, at around 85km, through a part of the country that I haven’t ridden much before.

We skirted Cranborne Chase & Wiltshire Downs National Landscape, with sweeping views and a glimpse of the famous Whestbury White Horse. The wind was now behaving in its usual prevailing direction, right into our face, and the day was marred by some heavy rain showers and badly-timed punctures. I was grateful for the company. I’m not sure Phil would have said the same when I bent my valve core and we lost a good hour trying to bend it straight enough to be pumped.

National Cycle Route 24 led us towards Bristol, where Phil lives, and we celebrated our arrival with a pint on the harbour. The temperature drove us inside before long, so we retreated to Phil’s where I stayed the night, before heading home the following morning. It was around 250 km until the next station with a direct connection to London, so I’d figure out that logistical riddle another time.

While I was grateful to be making the most of my final months on a discounted ‘young persons’ railcard, I was conscious of how much all this train-travel was costing me. Trains in the UK are not cheap, and my last few rides had not been particularly cheap day-trips. Also, my time in the country was running out, so I decided to take a couple days off work, to knock out the remaining 600 km in 4 days. A distance that wouldn’t be too awful, allowing me time to enjoy the scenery and take photos, without burning up too many days of annual leave.

Another fortnight later I made it happen; back on the early morning train to Bristol on a Friday with 4 days to blast it back home, praying that the weather would be a little kinder to me.

There is something incredibly exciting about cycling across the Severn Bridge into Wales. I did it twice a couple of years ago, on my way to-and-from Ireland on a 2,000 km loop. I chuckled as I pedalled over, remembering the time I’d driven with friends to a festival in Wales. One of them was American, and I’d asked her if she remembered to pack her passport as we neared the bridge. At first she looked confused, but when we all said ‘well of course you need it – it’s a different country!’ the colour had drained from her face extraordinarily quickly.

It gets hilly pretty fast once you’re on Welsh soil. Fast descents into the valleys of the Wye Valley National Landscape, followed by leg-burning climbs for big views across rolling green farmland punctuated by rapeseed fields.

I wasn’t in Wales for more than around 50 km before crossing the invisible border back into England. By the time I reached the Shropshire Hills, the sun was setting and the sky was lit up in incredible shades of pink. I hiked up Wart Hill in the last light, and rolled out my bivvy for the night. As I drifted off, I tried to think when the last time I slept in a bivvy was. Maybe the Dales Divide? It’s not normally my preferred way to sleep outside, but I wanted to pack really light this time. I wasn’t sure I had the legs to do 4 consecutive 100 mile days with ease, so the less weight slowing me down the better.

I’d hoped to wake up to a beautiful sunrise, from up on my hilltop, crowned in by the remnants of what I’d now learnt was an old Iron Age hill fort. But alas, low clouds were shrouding the landscape. It had been a surprisingly cold night and I’d regretted not bringing my liner.

I rolled down into Church Stretton where I wolfed down a massive breakfast, a routine that I’d repeat the next couple of mornings too. It was fun to replicate the efficiency of an ultra-distance race, without having to actually do twice the distance. Before I was next hungry, I’d reached the halfway point of The Giant Circle – the furthest point from London. From here it was just a long ride home.

The quiet lanes made for great riding but all the recent rain had left its toll and numerous of the roads were completely flooded. All passable, but not without getting your feet wet. The stretches that were dry were in such a bad state you’d definitely prefer being on a gravel bike or something with chunkier tyres.

Once I’d passed under Stoke-on-Trent, the flatter section came to an end and the hills ramped up once again. I stopped for an obligatory photo at the ‘Peak District’ National Park entrance sign, and enjoyed one of the best sections of the route for the rest of the afternoon. Picture postcard villages, with the odd tourist coach parked up just to spoil the feeling that you’d been transported back in time.

A worthwhile detour to Carsington Water took me along some hard packed gravel and away from the main road, before tackling the last few hills to the River Derwent. Once again, the sky was putting on quite a show, with a rainbow that faded into an orange and pink sunset. I found myself an unglamorous bivvy spot nestled in among the trees, and drifted off to watch the last light fade, with the silhouette of the bare trees above me looking like veins stretching out across the night sky.

The next day of riding, my sixth segment of the Giant Circle, was less exciting. As I cycled the northern ‘top’ of the loop the landscape noticeably flattened and slowly widened. Before long I was in Newark-on-Trent where my main priority was finding a bike shop to purchase some lube. My chain was making some horrible noises after navigating all the flooded roads yesterday.

I made a quick visit to the town’s castle ruins, where King John died in 1216. From there, heading east from the river Trent, it was all about the Fens.

The Fens are a naturally marshy section of England that stretch out, pancake flat, for many miles. Most of the fens were drained centuries ago, and now the region is supported agriculture via a system of drainage channels and dykes that divide the fields. As an area to travel, especially by bike, it’s a strange place indeed, quite unlike many other parts of the country and certainly unique compared to everything else on the Giant Circle. It’s a place that can play tricks on a tired mind, with endless straight roads that seem to go nowhere under big bubblegum could-filled skies.

The day I cycled from Grimsby to London was my first taste of riding the fens, and I can’t say I was desperate to return. And yet, there is something quite special about the region, especially if the winds are favorable (which they were to me on this occasion).

I’d ridden through many charming towns and villages on this route, enough for me to highly recommend the loop to anyone who’s curious to explore a little more of British architecture. Many of them totally idyllic, the types of setting that make you imagine spreading out on the village green with a scone, while watching the local cricket team play the day away.

But out here it was a different story. The towns looked sad and neglected, with no architectural interest worth noting. Wisbech was especially bleak. Strange, considering the capital of Cambridgeshire (Cambridge, how did you guess?) is anything but poor and boring. I stopped for dinner at a Chinese place at the edge of town, where some lads in Stone Island looked completely bemused to see me in filthy lycra scoffing a bowl of vegetable fried rice in the takeaway entrance while waiting for my phone to charge up. I didn’t hang around for long.

The landscapes were cool, particularly around the embankments of the Old and New Bedford Rivers – a controlled flooding zone that can be up to 2m underwater after heavy rain. I was relieved to find the road perfectly rideable, with the low sun bouncing off the surrounding marshland.

It’s hard to find places to camp out there, and I was glad to have my discreet bivvy that I could roll out in one of the few clusters of trees.

As I drifted off I heard some rustles within the leaves not too far from me. Some kind of animal was nearby, and it didn’t sound particularly small. I tried to ignore it, but a strange bark cut through the silence. And then another, and then another. What on earth was it? It sounded like something between a dog bark and a human shouting, neither of which were a breed I wanted to meet in this dark field. But it would not stop making its horrible noise, bark, after bark, after bark.

Thank God for the internet. I unlocked my phone in the darkness, hoping that it wasn’t actually a person that would see my face lit up in the night and Googled ‘do deer bark?’. Lo and behold, the first thing that popped up was an article about Muntjac deer, the only breed that do indeed bark. The article also said that they could bark all night, so I clambered out of my bivvy and shouted back, which sent the animal scampering off towards the marshes.

I was relieved in the morning that a) it was not raining and b) that it would be my final night waking up in the bivvy. A slug had left an impressive trail across my bag, and to my horror I noticed that it even stretched inside the hood as I packed up. Rain had been forecast to arrive in the morning, but I was up early enough to beat it. Ely was barely 15 km away, so I hoped that I could get there before the heavens opened.

A nasty amount of rain was forecast, so I hammered on my pedals, while opening up Google Maps on my phone. It wasn’t even 7am yet and it might not be that easy to find somewhere open. Just as the first few drops began to fall, I saw the most beautiful sight ahead of me. The Golden Arches, shining bright above a busy junction at the edge of town. I dived into the McDonalds, ordered a big breakfast and made myself comfortable as the rain arrived.

The storm was wild; huge gusts blowing across the car park with horizontal rain. It was my last day of cycling, but London felt a long way away, especially in the knowledge that the direct train from Ely only takes 90 minutes.

I waited and waited, before eventually being driven out by boredom. Ely Cathedral, was enough to keep me dry and entertained for another short stop, while the last of the heavy rain blew over.

The 40mph winds were a little unnerving, but at least they were only coming in from the side. British cycling really can be quite miserable and peculiar at times. At one point the rain turned to a hailstorm, with hail the size of small peas stinging my exposed thighs, driving me to hide under a pine tree for another weather-induced break. A puncture in the rain soured my mood further, which was then compounded further when my cleat broke, but by this point I’d committed to the remaining miles, leaving the train station behind and inching slowly towards the capital.

The day was a slog, and there was no obvious alternative on my Giant Circle than following the B184 back towards London. Perhaps it wouldn’t have bothered me on an ordinary road ride (I am, after all, used to cycling in and out of London), but it was rush hour and the traffic was unsettling after so many peaceful miles during the last few days of riding.

Eventually I did reach the suburbs of North London. The first red TFL bus stop was an unassuming monument, but a comforting one nonetheless, welcoming me back home. At Havering-atte-Bower a glimpse through the trees revealed a view of Dartford bridge and London’s skyline in the distance.

My route deliberately followed National Cycle Route 13 into East London. It’s a ghastly cycle route as it joins the start of London’s Cycleway 3 in Barking. Perfectly safe, but as you ride along the A13 the dim from the cars is uneasy on the ears. Occasionally you get to cross a tributary to the Thames, and get a brief insight into the city fringes where urban infrastructure meets nature, but otherwise it feels like being sucked into a giant machine, with Canary Wharf’s looming skyscrapers being the hub that hoovers all the surrounding traffic inwards.

I wanted to cross the Thames via the Woolwich Ferry, but a large sign read ‘closed due to high winds’. I wondered how often that happens. It was a pity because there is something I love about that boat ride, a free crossing that many Londoners have never heard of.

There’s an alternative that covers the exact same distance under the water, rather than above it. (Well, actually, there’s also the DLR – but there’s no fun in that). The Woolwich Foot Tunnel has been around for over a hundred years, but you’re not that likely to have used it unless you live in the area. It’s the ugly sibling of the nearby Greenwich foot tunnel (there’s only two pedestrian tunnels under the Thames) but is slightly longer and more quiet, making it a little eerie at the best of times.

On the South side of the Thames – my side of the river – it all suddenly seems worth it after that push through East London smog. I love the ride from Woolwich to Greenwich on this stretch of the river, along the path reserved only for pedestrians and cyclists. In some sections it’s well made and maintained, whereas in other parts it’s an ugly afterthought. It meanders along historical stretches of the river between industrial sights and brand spanking new apartment blocks. It’s a mad mix of everything I love about London, accompanied by Canary Wharf’s stunning skyline and you wiggle your way around the Milenium Dome. It’s not exactly straight, for the circle’s sake, but it is worth it for this almighty conclusion.

I pedalled past the Cutty Sark, and back up to Greenwich Observatory, from where I could look down on the stretch I’d cycled along the river as I neared the circle’s conclusion. What a special place to finish. And what an utterly pointless ride (pun intended). The Giant Circle was finally complete.

You can find the full route here.

One thought on “The Giant Circle: Cycling the Biggest Possible Loop in Britain (02/03/24-15/04/24)”